Archives Hub feature for March 2020

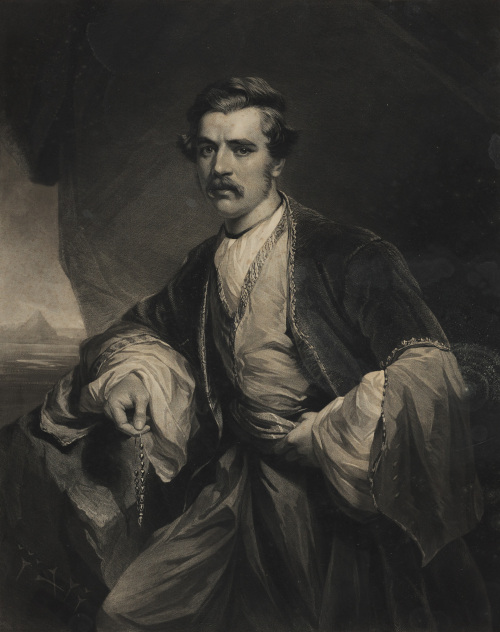

In 1839 a young lawyer left behind his London office for a post in the Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) Civil Service, thus beginning a series of travels, adventures and discoveries which would result in him achieving world renown for uncovering and shining a light on the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, in particularly Assyrian culture. That young man was Austen Henry Layard. This month Newcastle University’s Special Collections makes the catalogue to the Layard (Austen Henry) Archive available to researchers via the Archives Hub, along with that of another collection which shares a family provenance with the Layard Archive, the Blenkinsopp Coulson (William) Archive.

The Layard (Austen Henry) Archive

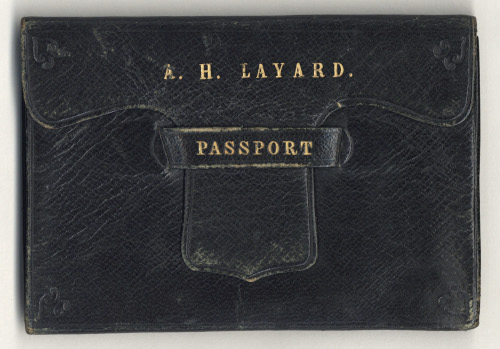

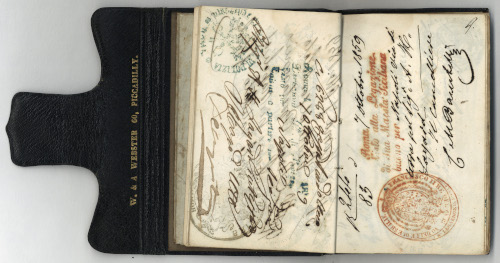

A typical Victorian polymath, Sir Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894) was an archaeologist, politician, and diplomat. The latter two of these roles he settled into in his later years; amongst his many achievements in the spheres of politics and diplomacy, he championed the cause of administrative reform in the Ottoman Empire and held ambassadorships to both Madrid (1869–1877) and Constantinople (1877–1880). Letters in the Layard Archive written by Layard’s wife Enid contain descriptions of his activities during those ambassadorships, including some dramatic descriptions of scenes witnessed by Enid during the Third Carlist War (1872–1876) and the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), and one of Layard’s passports held in the archive serves as a physical representation of his busy and dynamic career in this period.

But in the 1840s and 1850s, Layard’s great achievements were in the archaeological and cultural sphere, and it is this period of his life which is most greatly illuminated by the Layard Archive, as well as by the Layard book collection which is held alongside the archive.

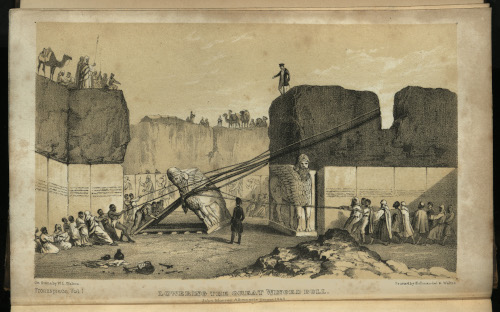

Having abandoned his plan to take up work in Ceylon and instead having been engaged by the British ambassador in Istanbul to carry out unofficial diplomatic missions, Layard became interested in locating and unearthing the great cities of biblical renown after spending time near Mosul, Ottoman Mesopotamia (now in Iraq). Mistaking Nimrud, site of the Assyrian capital of Calah, for Nineveh, he excavated there (1845–51) and discovered the remains of palaces of 9th– and 7th-century-BC kings and many important artworks. These included sculptures from the reign of King Ashurnasirpal II and a huge winged bull that remain among the most valued treasures of the British Museum. Layard published his discoveries in his book The Monuments of Nineveh (1849) and the later volume A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh (1853) and was hailed for shedding light on an ancient culture which hitherto had been completely lost.

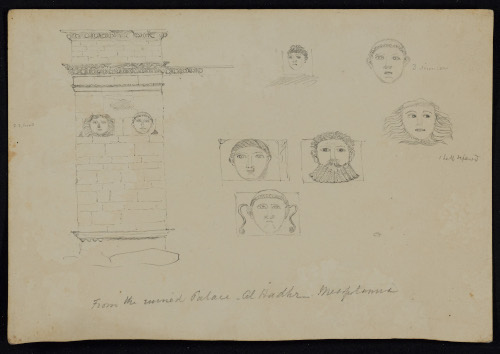

During his earlier travels and the excavations, Layard made detailed pencil sketches, many of which he used to create the engravings in his publications. One of the remarkable aspects of the Layard Archive is that it contains a huge number of these original sketches, often dog-eared and stained with dirt or ink, giving a vivid sense of their having been created on-site as working papers by Layard. There are detailed maps and plans of excavated buildings and temples, and annotated drawings of architectural and iconographic details, such as this sketch annotated by Layard as being “From the ruined Palace- Al Hadhr”.

Another wonderful sketch contained in the archive is the original version of arguably the most famous drawing to have been featured in Layard’s publications, that of the aforementioned great winged bull or lion, as Layard terms it in his annotation, from Nimrud.

Evidence elsewhere in the Layard Archive confirms that the Layard family once possessed Layard’s original sketch of the moving of the winged bull from Nimrud; the evidence is held in the form of a letter from the British Museum to a family member who donated the sketch to the Museum in 1960. In the letter (LAY/1/2/21) it is confirmed that the original sketch given to the Museum was the basis for another of Layard’s famous published engravings depicting the very same scene, although in its published form Layard has included himself, giving directions from the top of the ruins!

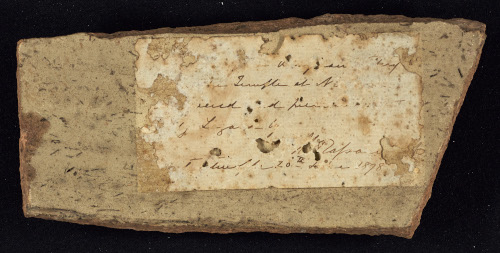

The Layard Archive also contains a number of objects, the most enigmatic and unusual of which is a shard of Assyrian pottery. Layard is known to have amassed his own private collection of archaeological objects, some of which he brought home himself, others of which were given to him, and many of which he eventually passed on to friends and relatives. This particular item was a gift to Layard from his fellow archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam who continued excavation work in Mesopotamia after Layard had ended his own work there. The label on its reverse shows that it came from a temple at Nimrud and historian Stefania Ermidoro has concluded that it is likely to form part of a larger vessel also excavated by Rassam and now in the British Museum.

The Layard (Austen Henry) Layard Archive, along with its associated book collection, shines much light onto 19th Century archaeology and discovery, and the dissemination of the knowledge of Assyrian culture in this period, whilst providing vivid insights into Layard’s archaeological research and methods, as well as other aspects of his illustrious career.

More can be read about the Layard Archive in Stefania Ermidoro’s article, The Latest Layard Archive: New Documents from Newcastle University published in Iraq (2019) 81 127-144.

The Blenkinsopp Coulson (William) Archive

The Blenkinsopp Coulson (William) Archive is linked with the Layard by a shared family provenance, although there the similarities end.

William Lisle Blenkinsopp Coulson (1841-1911) was a prominent figure in Newcastle upon Tyne, having established the Newcastle Dog and Cat shelter and been an early champion of animal rights. The Blenkinsopp Coulson Archive is his family collection; as well as a small amount of correspondence and printed matter relating to William himself, the archive also contains items which were passed down through his family, to William himself and then beyond him to his current descendants.

One item of particular interest is a recipe book compiled by Jane Blenkinsopp Coulson of Jesmond, now in Newcastle, dated 1733. The book contains a huge range of culinary and medicinal recipes which Jane likely acquired through her social networks in the local community. The title page reads: “Choice and Experienced Receipts of Cookery, Preserves, Conserves, Pickles, etc. together with a Collection of Valuable Receipts for Physick collected from Mr John Spearman of Hetton and other able and Eminent Physicians,” The example here, for Lady Allen’s cordial water, includes an amazing array of flowers, herbs and roots, from leaves of Meadow Sweet to roots of Snake Wort.

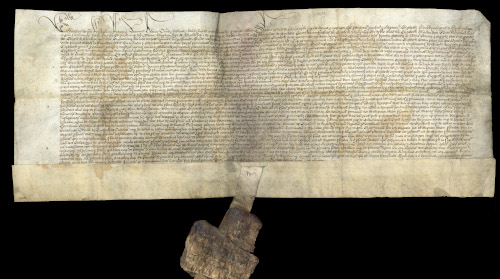

Also of note in the Blenkinsopp Coulson Archive is a General Pardon granted by King Edward IV to Elizabeth Blenkinsopp, dated 23rd April 1469. It is a fabulous example of Letters Patent bearing the Great Seal of Edward IV, densely packed with information in the form of archaic legal wording and terminology. Written in medieval Latin, the document offers fascinating glimpses into the medieval mindset and legal system as well as insights into a crucial chapter in the Wars of the Roses in England, the Siege of Harlech Castle (1461-1468), famous as the longest siege in British history.

Geraldine Hunwick

Senior Archivist

Special Collections, Newcastle University

Related

Layard (Austen Henry) Archive, 1817-1970

Blenkinsopp Coulson (William) Archive, 1469-1975

Browse all University of Newcastle Special Collections and Archives descriptions available to date on the Archives Hub.

Previous features on University of Newcastle Special Collections and Archives:

The Archives of the Trevelyans of Wallington

All images copyright University of Newcastle. Reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holders.